Peter Zumthor of Switzerland Becomes the 2009 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

Peter Zumthor of Switzerland has been chosen as the 2009 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The formal ceremony for what has come to be known throughout the world as architecture’s highest honor will be held on May 29 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. At that time, a $100,000 grant and a bronze medallion will be bestowed on the 65-year old architect.

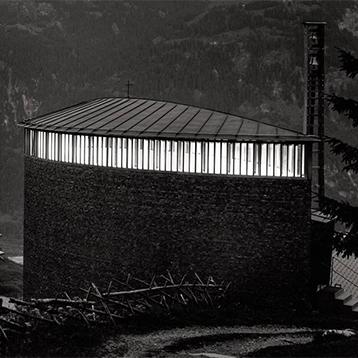

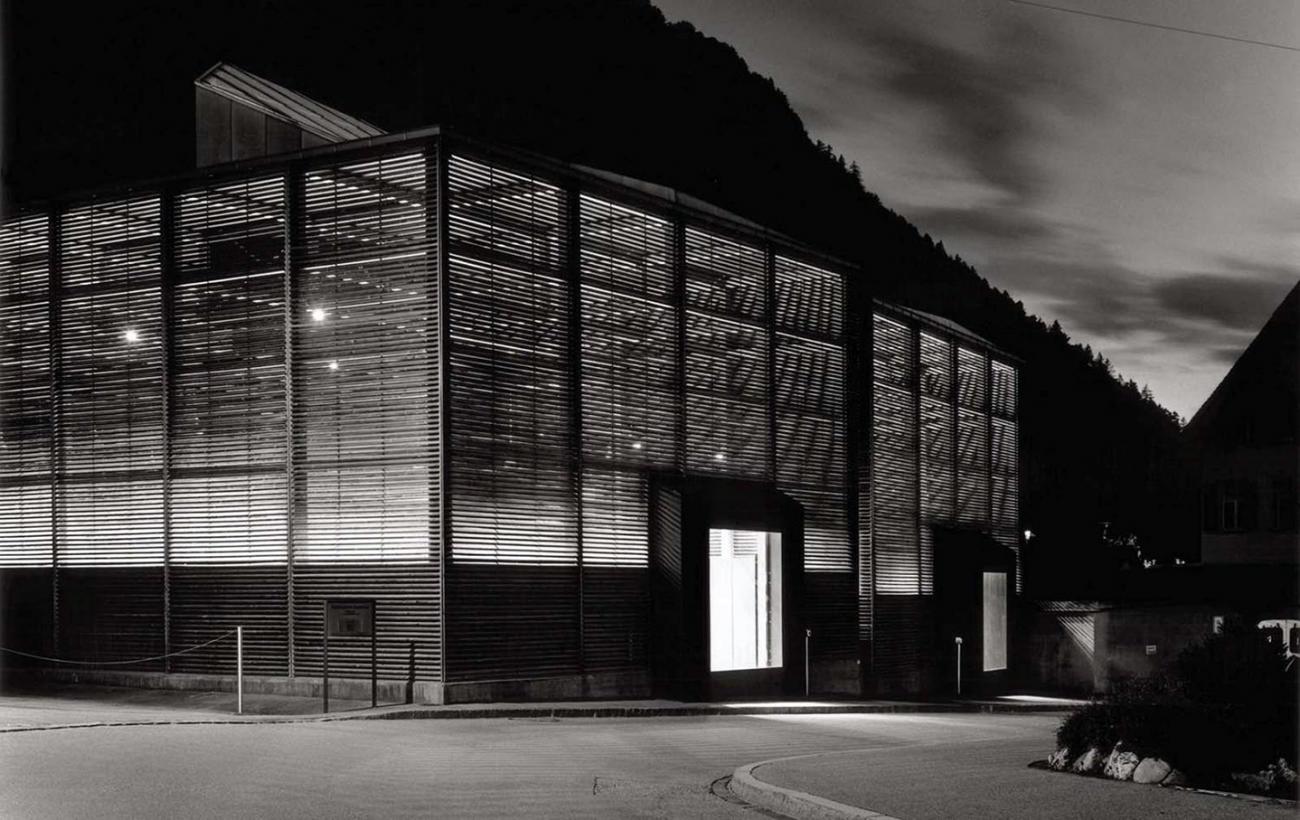

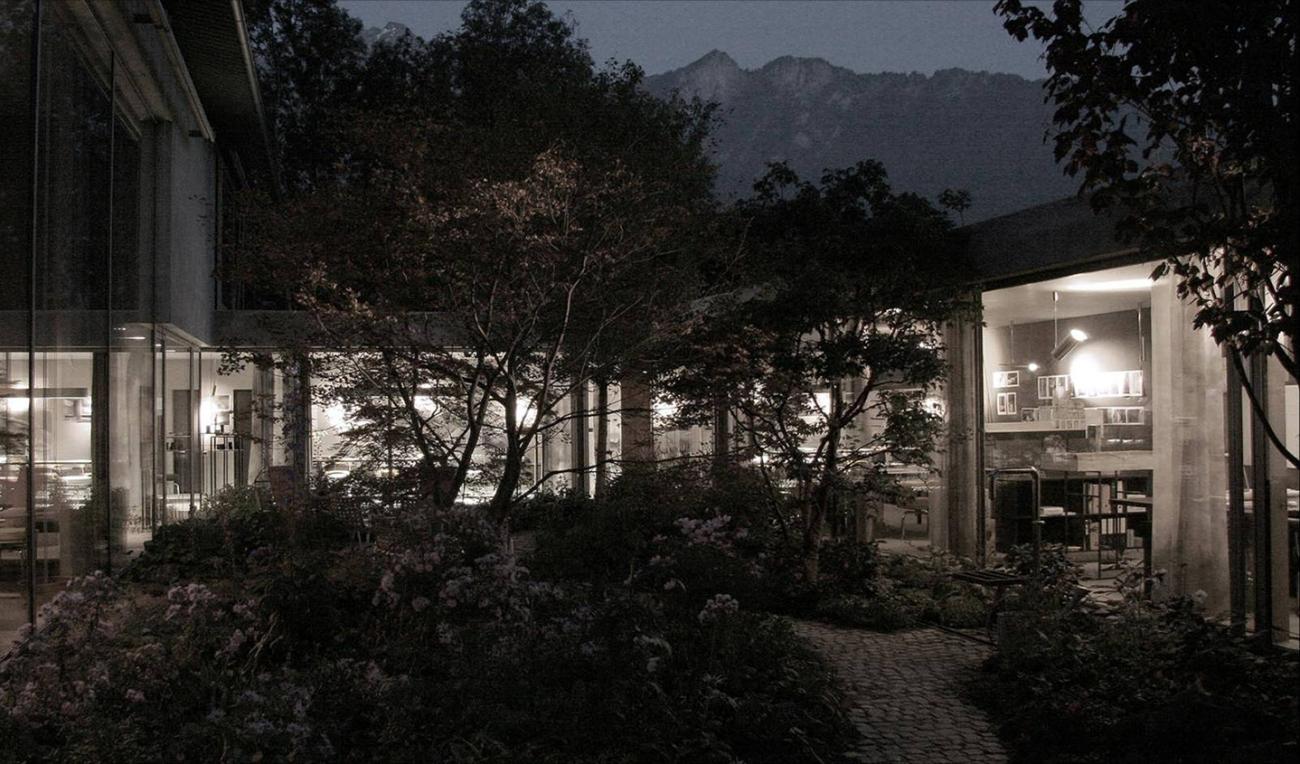

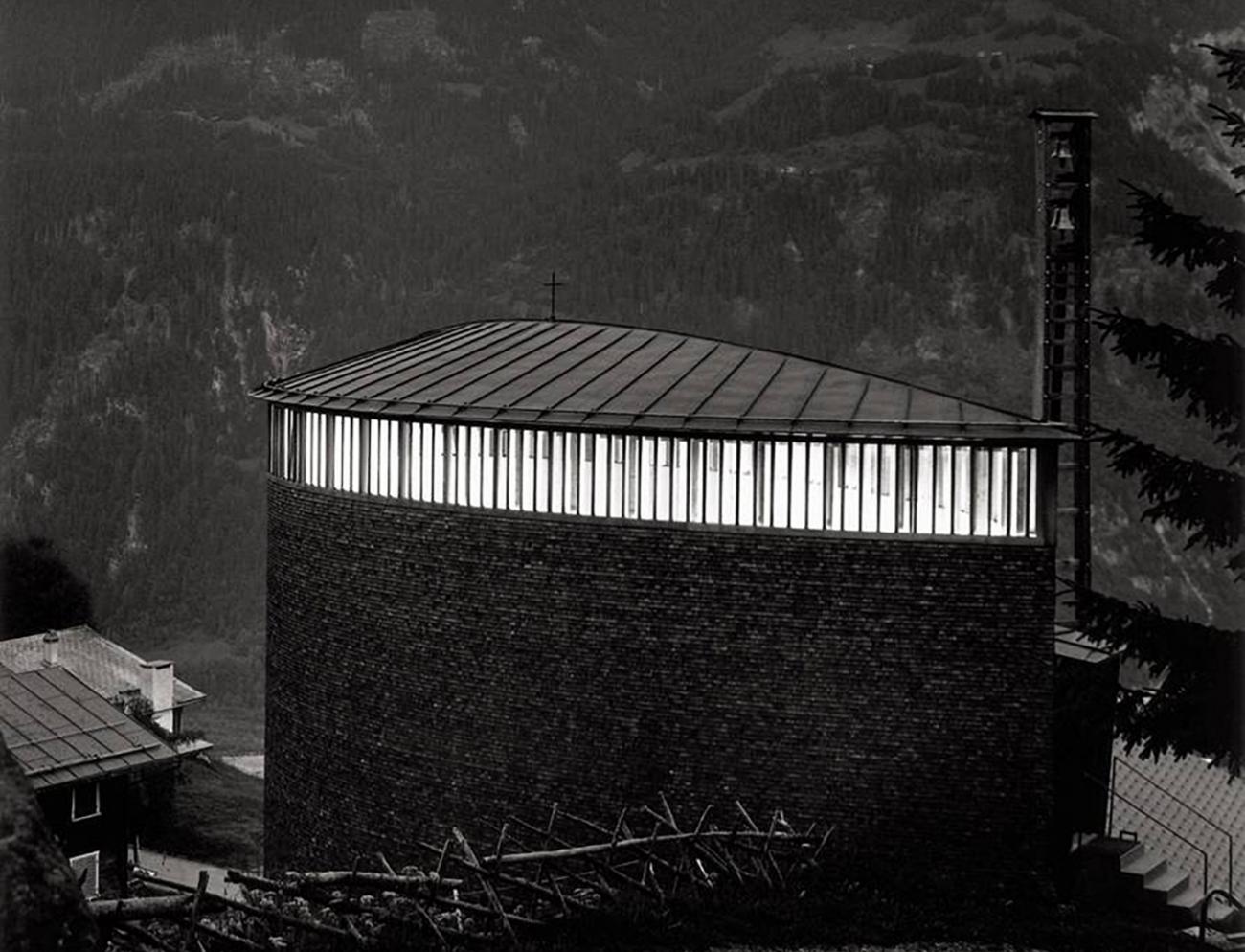

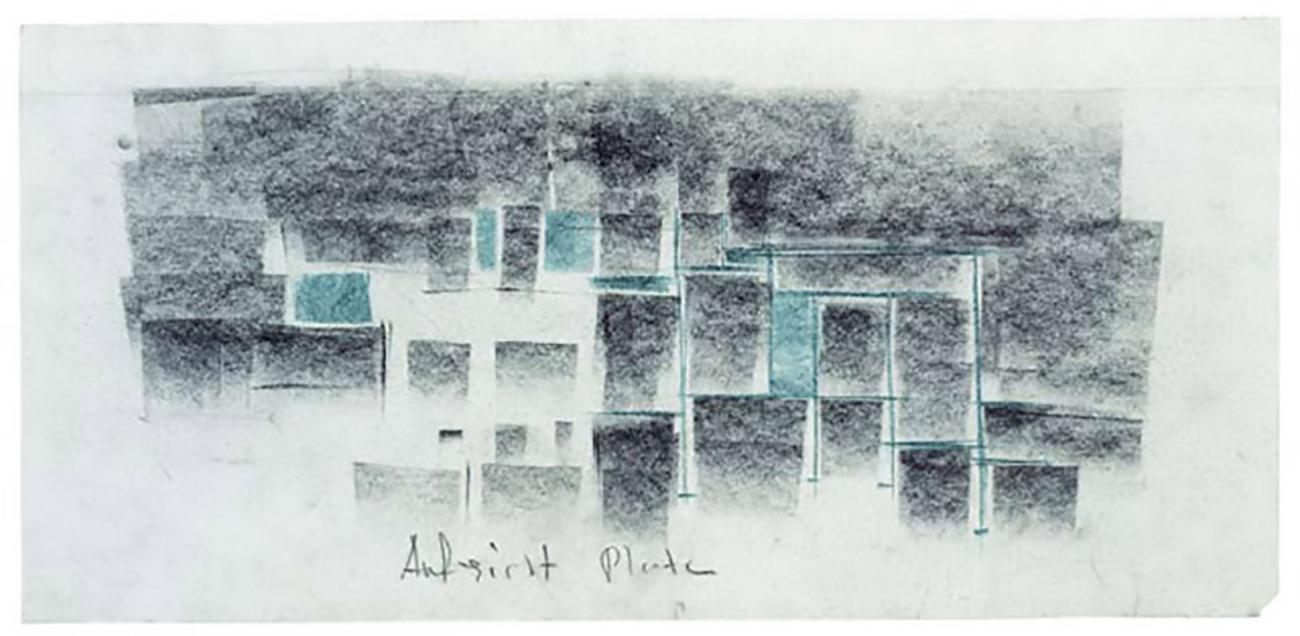

Although most of his work is in Switzerland, he has designed projects in Germany, Austria, The Netherlands, England, Spain, Norway, Finland and the United States. His most famous work is in Vals, Switzerland—the Thermal Baths, which has been referred to by the press as “his masterpiece.” Most recently critics have praised his Field Chapel to Saint Nikolaus von der Flüe near Cologne, Germany. The jury singled out not only those buildings, but also the Kolumba Museum in Cologne, calling the latter “a startling contemporary work, but also one that is completely at ease with its many layers of history.”

In announcing the jury’s choice, Thomas J. Pritzker, chairman of The Hyatt Foundation, quoted from the jury citation, “Peter Zumthor is a master architect admired by his colleagues around the world for work that is focused, uncompromising and exceptionally determined.” And he added, “All of Peter Zumthor’s buildings have a strong, timeless presence. He has a rare talent of combining clear and rigorous thought with a truly poetic dimension, resulting in works that never cease to inspire.”

In Zumthor’s own words as expressed in his book, Thinking Architecture, “I believe that architecture today needs to reflect on the tasks and possibilities which are inherently its own. Architecture is not a vehicle or a symbol for things that do not belong to its essence. In a society that celebrates the inessential, architecture can put up a resistance, counteract the waste of forms and meanings, and speak its own language. I believe that the language of architecture is not a question of a specific style. Every building is built for a specific use in a specific place and for a specific society. My buildings try to answer the questions that emerge from these simple facts as precisely and critically as they can.”

Pritzker Prize jury chairman, The Lord Palumbo elaborated with more of the citation: “Zumthor has a keen ability to create places that are much more than a single building. His architecture expresses respect for the primacy of the site, the legacy of a local culture and the invaluable lessons of architectural history.” He continued, “In Zumthor’s skillful hands, like those of the consummate craftsman, materials from cedar shingles to sandblasted glass are used in a way that celebrates their own unique qualities, all in the service of an architecture of permanence.”

The Zumthor choice marks the second time in three decades of the Pritzker Architecture Prize that Switzerland has provided the laureate. In 2001, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron were the honorees.

The purpose of the Pritzker Architecture Prize is to honor annually a living architect whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.

The distinguished jury that selected Zumthor as the 2009 Laureate consists of its chairman, Lord Palumbo, internationally known architectural patron of London, chairman of the trustees, Serpentine Gallery, former chairman of the Arts Council of Great Britain, former chairman of the Tate Gallery Foundation, and former trustee of the Mies van der Rohe Archive at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and alphabetically: Alejandro Aravena, architect and executive director of Elemental in Santiago, Chile; Shigeru Ban, architect and professor at Keio University, Tokyo, Japan; Rolf Fehlbaum, chairman of the board, Vitra in Basel, Switzerland; Carlos Jimenez, professor, Rice University School of Architecture, principal, Carlos Jimenez Studio in Houston, Texas; Juhani Pallasmaa, architect, professor and author of Helsinki, Finland; Renzo Piano, architect and Pritzker Laureate, of Paris, France and Genoa, Italy; and Karen Stein, writer, editor and architectural consultant in New York. Martha Thorne, associate dean for external relations, IE School of Architecture, Madrid, Spain, is executive director.

By the first decades of the 20th century, Argentina ranked among the richest countries in the world. This amazing progress was set in motion by the Generation of the ‘80s, statesmen determined to build a replica of modern Europe in Argentina with Buenos Aires symbolizing this dream. It's not surprising that many of the buildings constructed in Argentina during the last decades of the 19th century and in the early 20th century looked to European models for inspiration. The Legislative Palace in the city of Buenos Aires is but one example. Designed by Héctor Ayerza (1893-1949), who trained in Buenos Aires and France, it was built between 1927 and 1931 in Louis XIV neoclassical style. The heart of the building is the Sessions Chambers and its many sumptuous salons. The Salon Dorado (Golden Salon), inspired by the Palace of Versailles and specifically the Gallery of Mirrors, is perhaps the most famous of these salons.

By the first decades of the 20th century, Argentina ranked among the richest countries in the world. This amazing progress was set in motion by the Generation of the ‘80s, statesmen determined to build a replica of modern Europe in Argentina with Buenos Aires symbolizing this dream. It's not surprising that many of the buildings constructed in Argentina during the last decades of the 19th century and in the early 20th century looked to European models for inspiration. The Legislative Palace in the city of Buenos Aires is but one example. Designed by Héctor Ayerza (1893-1949), who trained in Buenos Aires and France, it was built between 1927 and 1931 in Louis XIV neoclassical style. The heart of the building is the Sessions Chambers and its many sumptuous salons. The Salon Dorado (Golden Salon), inspired by the Palace of Versailles and specifically the Gallery of Mirrors, is perhaps the most famous of these salons. Originally the Palacio Anchorena, Palacio San Martin was purchased by the Ministry of Foreign Relations in 1936 and named in honor of José de San Martín, the leader of the independence of Argentina. Designed in 1906 by architect Alejandro Christophersen (1866-1946), it was conceived as a “hotel particular,” containing three residences organized around a central patio. The architecture, as in many residences of wealthy Argentine families at that time, is historicist eclecticism, and in the early years of the 20th century, the influence was clearly French. It combines organizational elements of classicism along with the lyricism of Art Nouveau. The architect, whose father was in the Norwegian diplomatic corps, was born in Spain, trained in Paris and Antwerp, and settled in Argentina soon after completing his studies. In an almost sculptural way, the Palacio combines convex mansards, cupolas, chimneys, columns, and balconies. The central patio or cour d’honeur has an impressive double staircase that led to the individual residences. In addition to the famous Palacio San Martin, Alejandro Christophersen designed other notable residences, hotels, banks, and offices and is also known for his paintings, teaching, and writings.

Originally the Palacio Anchorena, Palacio San Martin was purchased by the Ministry of Foreign Relations in 1936 and named in honor of José de San Martín, the leader of the independence of Argentina. Designed in 1906 by architect Alejandro Christophersen (1866-1946), it was conceived as a “hotel particular,” containing three residences organized around a central patio. The architecture, as in many residences of wealthy Argentine families at that time, is historicist eclecticism, and in the early years of the 20th century, the influence was clearly French. It combines organizational elements of classicism along with the lyricism of Art Nouveau. The architect, whose father was in the Norwegian diplomatic corps, was born in Spain, trained in Paris and Antwerp, and settled in Argentina soon after completing his studies. In an almost sculptural way, the Palacio combines convex mansards, cupolas, chimneys, columns, and balconies. The central patio or cour d’honeur has an impressive double staircase that led to the individual residences. In addition to the famous Palacio San Martin, Alejandro Christophersen designed other notable residences, hotels, banks, and offices and is also known for his paintings, teaching, and writings.