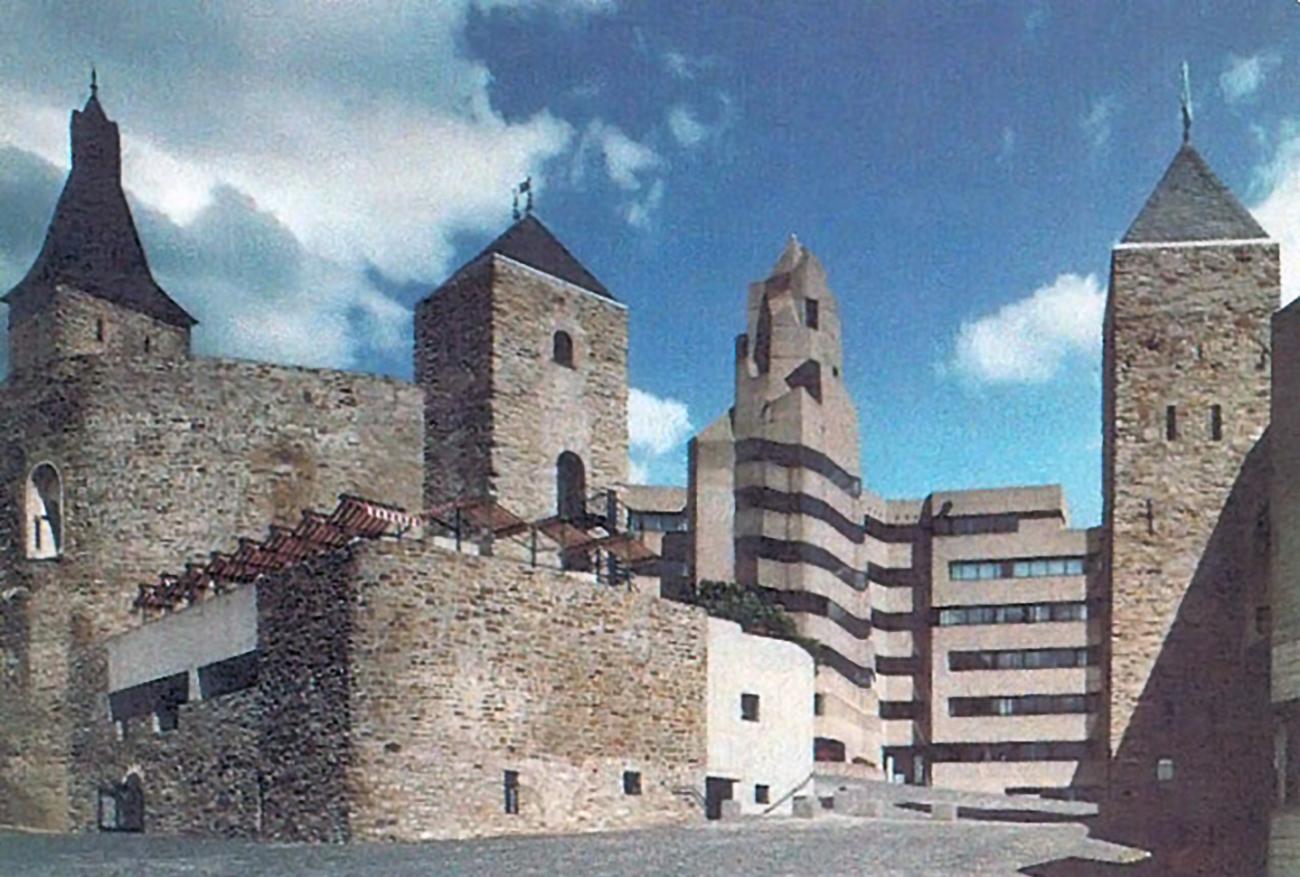

The work of Gottfried Böhm (1920–2021) ranges from the simple to the complex, using many different kinds of materials, with results that sometimes appear humble, sometimes monumental. He has been described in the sixties as an expressionist, and more recently as post-Bauhaus, but almost always he stands alone in departing from the conventions of established architecture, seeking to go one step beyond.

Böhm himself prefers to be thought of in terms of creating "connections"—for example, the integration of the old with the new, the world of ideas with the physical world, the interaction between the architecture of a single building with the urban environment, taking into account the form, material, and color of a building in its setting.

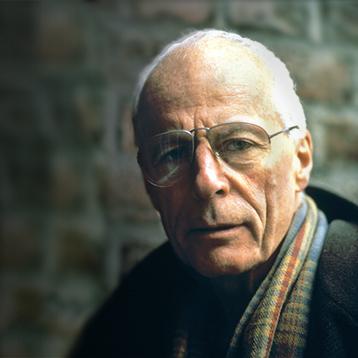

Gottfried Böhm was born in Offenbach-am-Main on January 23, 1920, the son of Dominikus Böhm, one of Europe's most respected architects of Roman Catholic churches and ecclesiastical buildings. Since his paternal grandfather had been an architect as well, it is not surprising that Gottfried started on that path.

His academic career began in 1942, when he attended the Technische Hochschule in Munich. He received degree in 1946. For another year, he continued his education, studying sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. That training has been important for the clay models he develops during the design process of his buildings.

He worked in his father's office as an assistant architect from 1947to1950. During that time he collaborated with the Society for the Reconstruction of Cologne under the direction of Rudolph Schwarz. In 1948, he met and married Elisabeth Haggenmueller, who is also a licensed engineer and architect. They have four sons, three of whom have become architects.

Feeling the need for other points of view, in 1951, Böhm journeyed to New York where he worked in the architectural firm of Cajetan Baumann for six months. Several more months were spent on a study tour of the United States, during which time he had the opportunity to meet Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, two of the architects for whom he holds great admiration.

His study tour over, Böhm returned to work with his father in 1952. His father's influence plus the ideas and theories of Bauhaus, were apparent in his first independent projects. Nevertheless, his multiple skills enabled him to overcome this phase quickly. He did not discover a different style; what he discovered was a clear conviction of the importance of every single architectural assignment, no matter how small, and he learned that, along with the factors of time and place, man is the most important value to be taken into consideration."