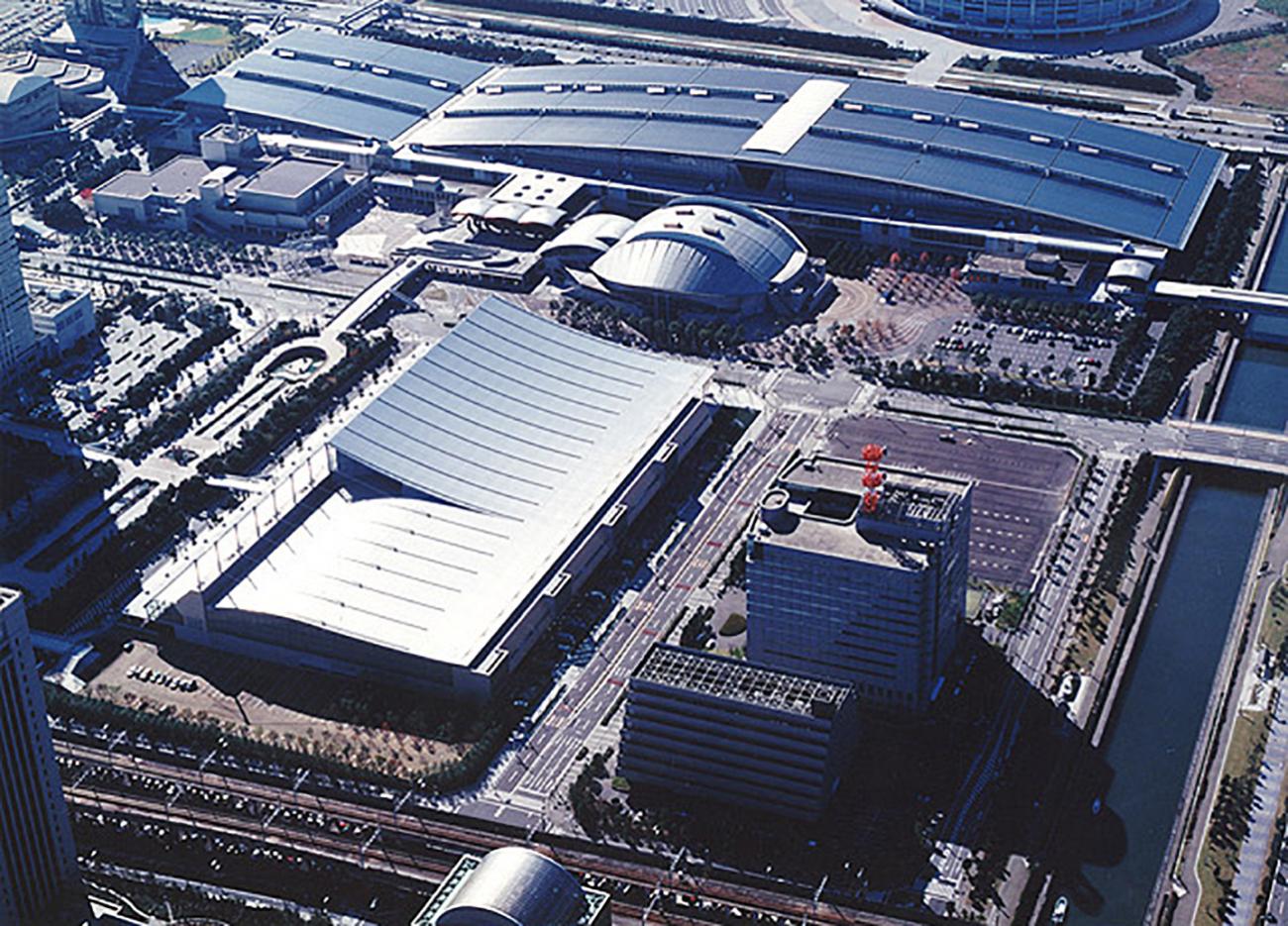

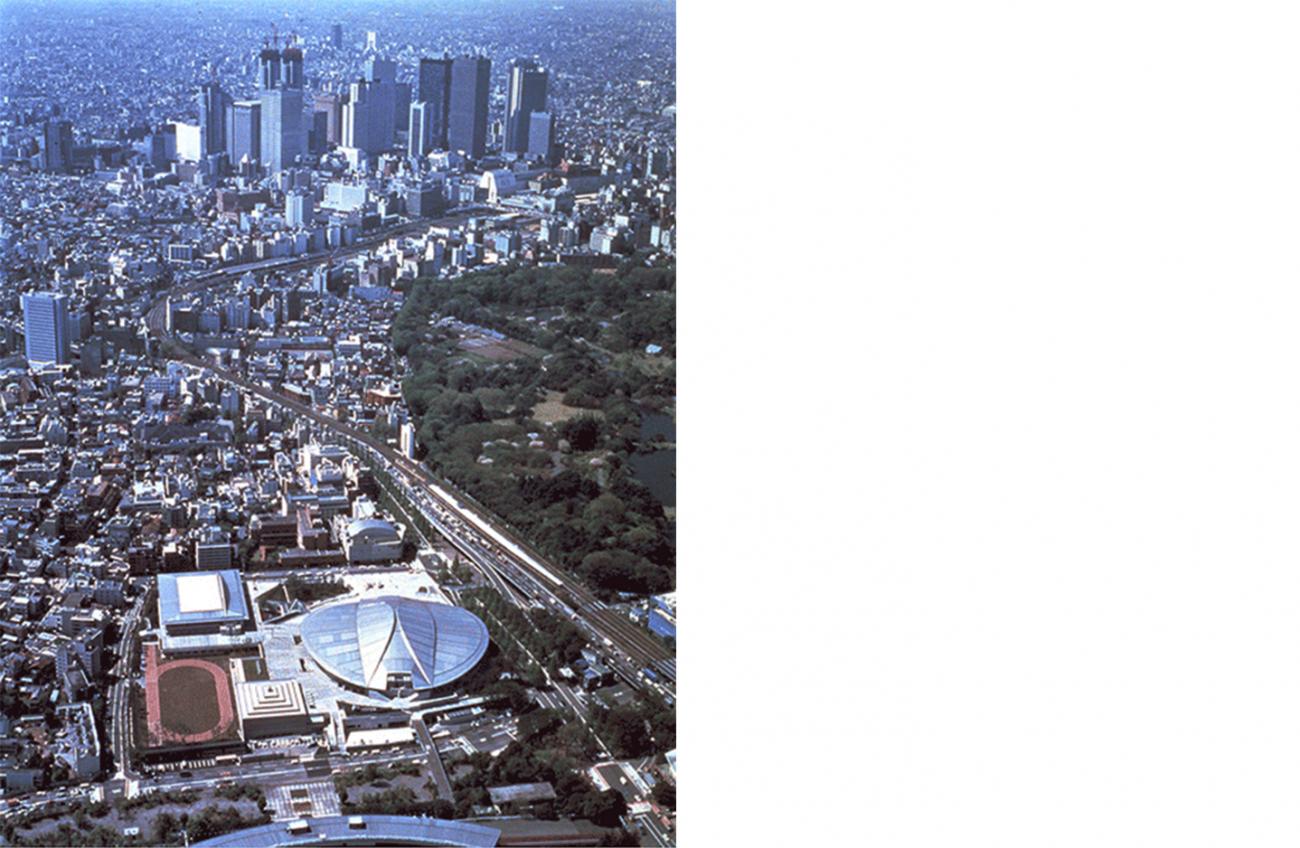

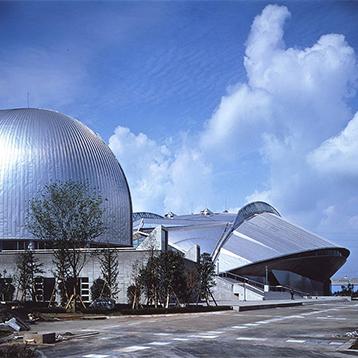

Fumihiko Maki (1928 - 2024) calls himself a modernist, unequivocally. His buildings tend to be direct, at times understated, and made of metal, concrete and glass, the classic materials of the modernist age, but the canonical palette has also been extended to include such materials as mosaic tile, anodized aluminum and stainless steel. Along with a great many other Japanese architects, he has maintained a consistent interest in new technology as part of his design language, quite often taking advantage of modular systems in construction. He makes a conscious effort to capture the spirit of a place and an era, producing with each building or complex of buildings, a work that makes full use of all that is presently at his command. Maki often speaks of the idea of creating "unforgettable scenes"—in effect, settings to accommodate and complement all kinds of human interaction—as the inspiration and starting point for his designs.

Maki, who was born in Tokyo, studied with Kenzo Tange at the University of Tokyo where he received his Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1952. Maki then spent the next year at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. After completing a Master of Architecture degree at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), Harvard University, he apprenticed at the firms Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, New York and Sert Jackson and Associates in Cambridge.

In 1956, he took a post as assistant professor of architecture at Washington University in St. Louis, where he also received his first design commission—for the Steinberg Hall (an art center) on that campus. Following his four years there, he joined the faculty at Harvard's GSD from 1962 to 1965, and has been a frequent guest lecturer at numerous other universities.

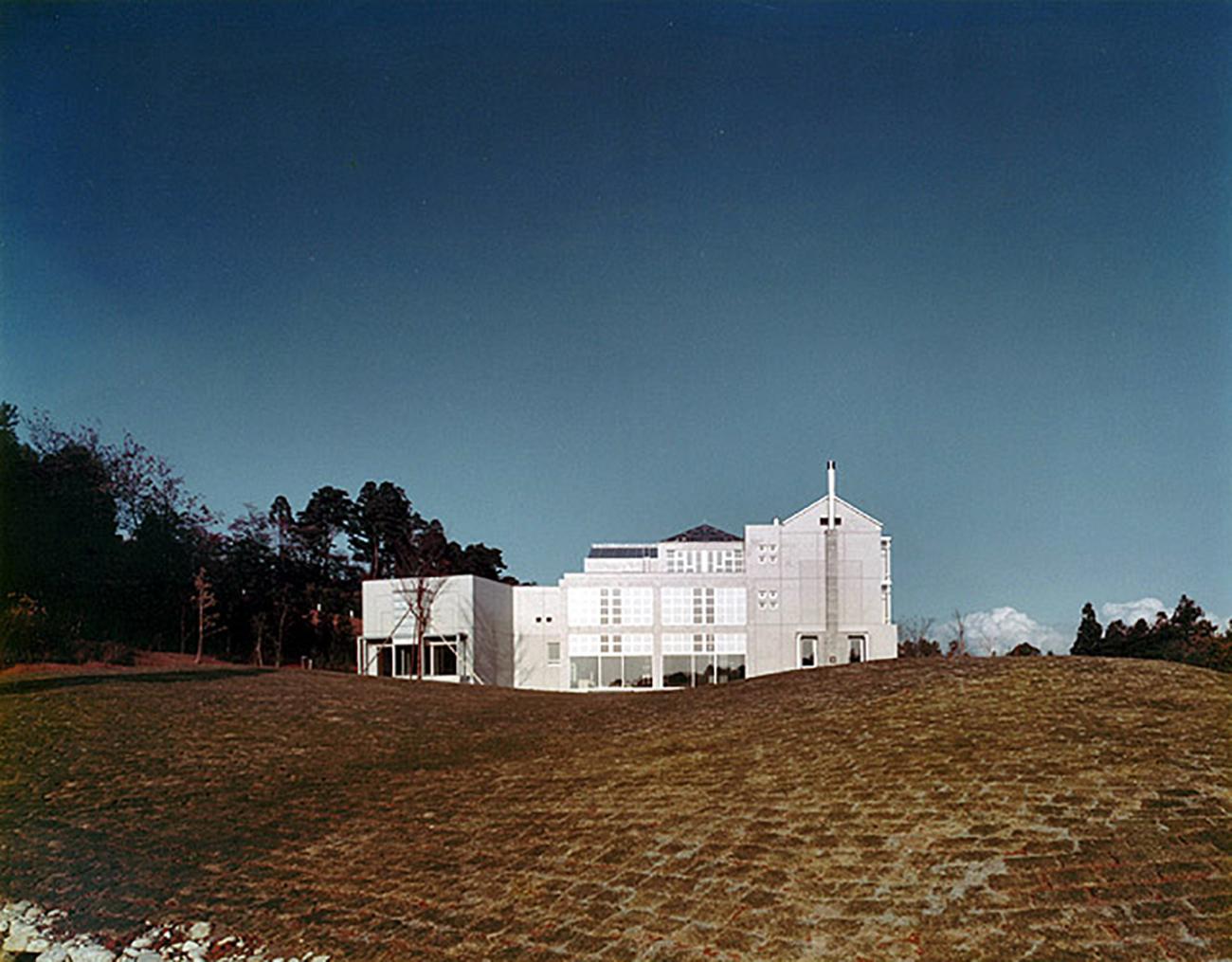

In 1965, he returned to Japan to establish his own firm, Maki and Associates in Tokyo. In the 28 years since, his staff has grown to approximately 35 people, with an equal number having passed through to begin their own practices. "I was never attracted to the idea of a large organization. On the other hand, a small organization may tend to develop a very narrow viewpoint. My ideal is a group structure that allows people with diverse imaginations, that often contradict and are in conflict with one another, to work in a condition of flux, but that also permits the making of decisions that are as calculated and objectively weighed as necessary for the creation of something as concrete as architecture."