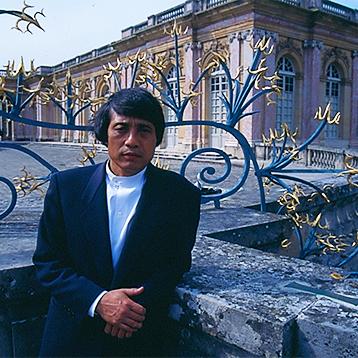

Tadao Ando of Osaka, Japan is a man who is at the pinnacle of success in his own country. In the last few years, he has emerged as a cultural force in the world as well. In 1995, the Pritzker Architecture Prize was formally presented to him within the walls of the Grand Trianon Palace at Versailles, France. There is little doubt that anyone in the world of architecture will not be aware of his work. That work, primarily in reinforced concrete, defines spaces in unique new ways that allow constantly changing patterns of light and wind in all his structures, from homes and apartment complexes to places of worship, public museums and commercial shopping centers.

“In all my works, light is an important controlling factor,” says Ando. “I create enclosed spaces mainly by means of thick concrete walls. The primary reason is to create a place for the individual, a zone for oneself within society. When the external factors of a city’s environment require the wall to be without openings, the interior must be especially full and satisfying.”

And further on the subject of walls, Ando writes, “At times walls manifest a power that borders on the violent. They have the power to divide space, transfigure place, and create new domains. Walls are the most basic elements of architecture, but they can also be the most enriching.”

Ando continues, “Such things as light and wind only have meaning when they are introduced inside a house in a form cut off from the outside world. I create architectural order on the basis of geometry squares, circles, triangles and rectangles. I try to use forces in the area where I am building, to restore the unity between house and nature (light and wind) that was lost in the process of modernizing Japanese houses during the rapid growth of the fifties and sixties.”

John Morris Dixon of Progressive Architecture wrote in 1990: “The geometry of Ando’s interior plans, typically involving rectangular systems cut through by curved or angled walls, can look at first glance rather arbitrary and abstract. What one finds in the actual buildings are spaces carefully adjusted to human occupancy.” Further, he describes Ando’s work as reductivist, but “… the effect is not to deprive us of sensory richness. Far from it. All of his restraint seems aimed at focusing our attention on the relationships of his ample volumes, the play of light on his walls, and the processional sequences he develops.”

In his childhood, he spent his time mostly in the fields and streets. From ages 10 to 17, he also spent time making wood models of ships, airplanes, and moulds, learning the craft from a carpenter whose shop was across the street from his home. After a brief stint at being a boxer, Ando began his self-education by apprenticing to several relevant persons such as designers and city planners for short periods. “I was never a good student. I always preferred learning things on my own outside of class. When I was about 18, I started to visit temples, shrines, and tea houses in Kyoto and Nara, there’s a lot of great traditional architecture in the area. I was studying architecture by going to see actual buildings, and reading books about them. “ He made study trips to Europe and the United States in the sixties to view and analyze great buildings of western civilization, keeping a detailed sketch book which he does even to this day when he travels.