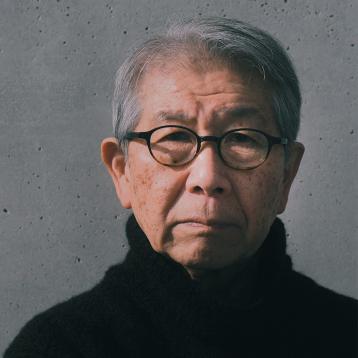

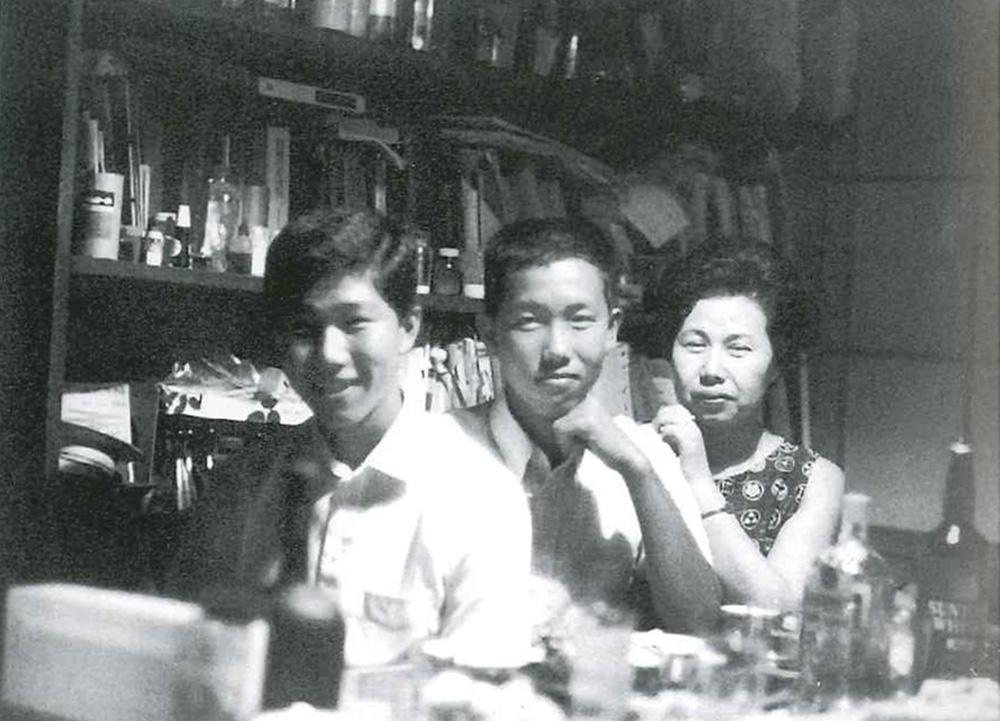

Japanese architect Riken Yamamoto (b. 1945) was born in Beijing, People’s Republic of China and relocated to Yokohama, Japan shortly after the end of World War II. Negotiating a balance between public and private dimensions from childhood, he lived in a home that was modeled after a traditional Japanese machiya, with his mother’s pharmacy in the front and their living area in the rear. “The threshold on one side was for family, and on the other side for community. I sat in between.”

Yamamoto knew little about his father, who had passed away when the architect was only five years old. In some ways, he sought to emulate his father’s career as an engineer, but instead forged his own path into architecture. At age 17, he visited Kôfuku-ji Temple, in Nara, Japan, originally built in 730 and finally reconstructed in 1426, and was captivated by the Five-storied Pagoda symbolizing the five Buddhist elements of earth, water, fire, air and space. “It was very dark, but I could see the wooden tower illuminated by the light of the moon and what I found at that moment was my first experience with architecture.”

He graduated from Nihon University, Department of Architecture, College of Science and Technology in 1968 and received a Master of Arts in Architecture from Tokyo University of the Arts, Faculty of Architecture in 1971. He founded his practice, Riken Yamamoto & Field Shop in 1973.

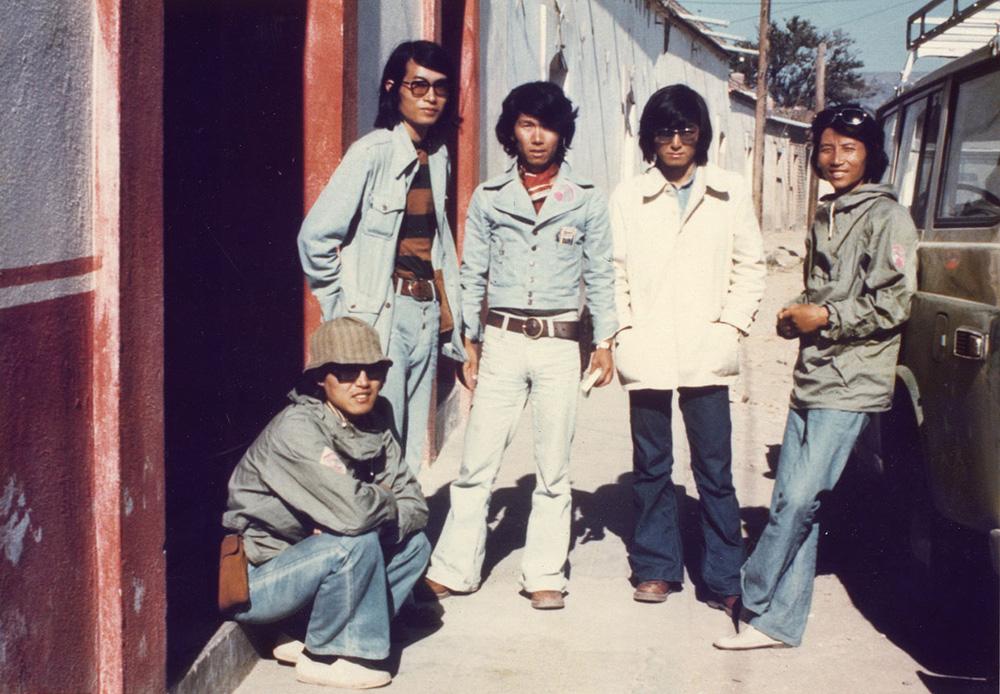

During the earliest years of his career, the architect spontaneously journeyed across countries and continents by car with his mentor, Hiroshi Hara, spending months at a time in pursuit of understanding communities, cultures and civilizations. In 1972, he drove along the coastline of the Mediterranean Sea, visiting France, Spain, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Italy, Greece and Türkiye. Two years later, he traveled from Los Angeles to Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica and Colombia before reaching Peru. He would also embark on a similar expedition to Iraq, India and Nepal, and concluded that the idea of a “threshold” between public and private spaces was universal. “I recognize the past system of architecture is so that we can find our culture...The villages were different in their appearance, but their worlds [were] very similar.”

Yamamoto reconsidered boundaries between public and private realms as societal opportunities, committing to the belief that all spaces may enrich and serve the consideration of an entire community, and not just those who occupy them. With this in mind, he began designing single-family residences that united natural and built environments, welcoming to both guests and passersby. His first project, Yamakawa Villa (Nagano, Japan 1977), is exposed on all sides and situated in the woods, designed to feel entirely like an open-air terrace. The experience significantly influenced his future works as he extended into social housing with Hotakubo Housing (Kumamoto, Japan 1991), bridging cultures and generations through relational living.